Mexico City on Fire: How the Streets Seized the Big Shots

Mexico City has had a stormy few days, marking the 10th anniversary of the brutal Ayotzinapa case. The capital's streets have gone up in flames — a threat to those who reign within its walls.

It was Monday noon, a bit early for lunch in Mexico, but I needed some air to fight off the dullness. I was just fixing my hangover with broth at a street food restaurant in the Juárez district, where they serve a four-course menu for 5 bucks, when Ricardo called me. The guy who was kind of responsible for my current state. What the hell does he want? I mean, we just met last night! I finally picked up the phone.

"Checo!" he shouted, the name I'm called around here by those who can't remember my real name or can't pronounce it. It doesn't matter in the end; I've gotten used to it.

"What's up, Ricardo?"

"Did you hear the explosions? Terrible blasts! Several in a row. Petardaaaazos!"

"No. I don't know anything. Where?"

"'Twas terribly powerful detonations here in Juarez. Now there's smoke rising from here, at the Ministry of the Interior. I just thought you might be interested. Maybe it was those from Ayotzinapa," he said, and I regretted suspecting him of being annoying.

Of course, I was interested. I just paid and ran that way. The Secretaría de Gobernación, or SEGOB, is only about two blocks from my apartment.

It was a bummer that I was having lunch in the opposite direction just then. I got there just to be passed by the returning TV crews. Photographers were sitting on the sidewalk, racing to see who could send the pictures to the newsrooms first. Talking heads were repeating stand-ups in front of the building, with only a few National Guard men and women stomping by in boredom. I missed the best part.

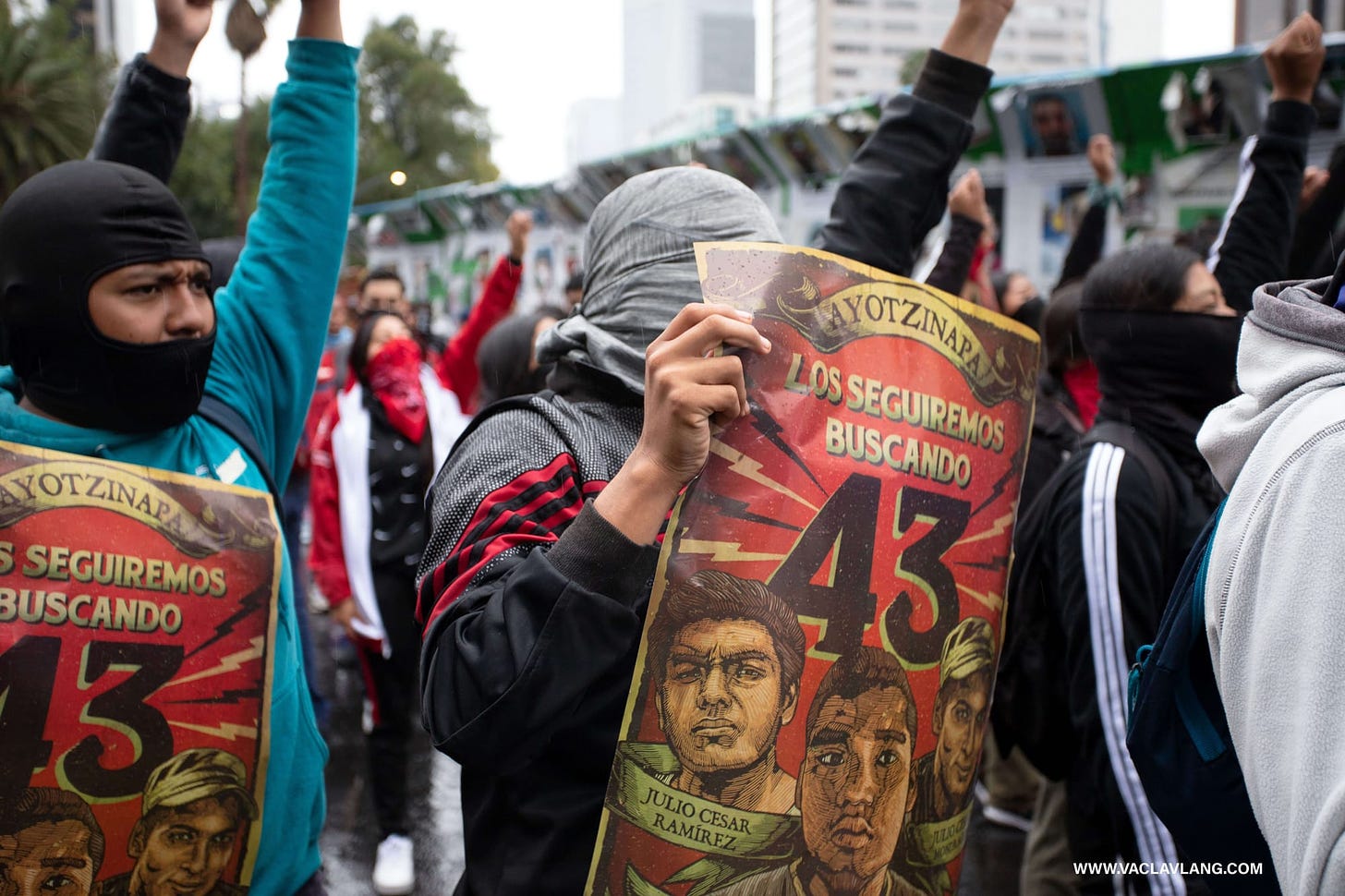

At least there's something left as a memento: walls spray-painted with the obligatory "43" and "Vivos se los llevaron, vivos los queremos!"—"They took them alive, we want them back alive!" So yes, it was "those from Ayotzinapa"; this is their signature.

As I soon learned, there were about eight shots fired before I arrived. Homemade explosives embedded in PVC tubes flew from the street behind the high fence of the office, blew out the windows, and caused a bit of a disturbance. So the protests began— a little earlier and a little more intense than I had anticipated.

Unexpected Party

But to get back to the beginning of the story. On Sunday evening, I was wandering around the darkening Juárez, sort of casually, not wanting to go home, until I decided to carry on an old tradition. This consisted of going at this time of the week to sit down and have one or two of the "better" beers from the local microbreweries. It was my recipe for beating the depression from the ending weekend, also known as the Sunday afternoon blues. Just to make that last-minute Sunday a little bit more pleasant.

So, I snuck into a nearby pub and, over an IPA from the local hipster district, dug into the articles and news that had caught my eye during the week. Two other guys were sitting there, just like me. We were each quietly drinking at our own tables, minding our own business. It didn't go unnoticed when one of them approached the other with the words, "You're a publicist, aren't you?" ...and put a magazine in front of him. "That's what we just published. What do you think?"

I soon felt like I was at a sort of journalism meeting. I tried not to listen for a while, but then I couldn't stand it. "Are you journalists?" I asked when their talk about papers stopped for a moment. They weren't. One of them, Niklas from Finland, who had lived in Mexico a little longer than I had, owned a marketing agency. The other, who had come to him for advice, was named Ricardo and lived nearby. I don't remember exactly what he had to do with the magazine he brought. Anyway, they invited me to join them, and we started to think together about what could be improved with the magazine—how to make the pages better, where to put the headlines next time, and so on.

The planned two beers suddenly became "I don't know how many" beers. We remained till closing time and sorted out a lot more than just the type fonts and colors. We discussed life in Mexico, politics, the upcoming change of presidents and government, and so on. I mentioned that it would now be ten years since the Ayotzinapa incident on Thursday, September 26, and that I expected things to heat up in the city. "Yeah, it's definitely going to be wild," Ricardo nodded.

We had time to exchange numbers before we were kicked out at around midnight, and we each slipped away to our own homes.

This unexpected party resulted in me being somewhat useless on Monday morning. But I did come away with some new knowledge and interesting contacts. Who knows, maybe they'll come in handy someday, I thought as I went to fix myself with broth at noon. And then the explosions at SEGOB and the inscriptions in memory of the 43 missing students happened. And the phone call from Ricardo.

The Scar Called Ayotzinapa

The case of Ayotzinapa is so extensive that it could be taught as a year-long course in college. It probably is. It is so important for illustrating what is happening in today's Mexico. No other case shows in direct light what the state-narco-crime nexus is really like here. But it is also quite complex, so for our purposes, I will describe it only in the most important outlines. For those who want to know more, I recommend the Netflix documentary Ayotzinapa: El paso de la tortuga.

The rural school Ayotzinapa (that's its name) in the south of Mexico is a specific institution with a long tradition of educating future cantors, and as a school in a humble area, it is also very community-based.

Like other similar rural pedagogical schools, it is characterized by, among other things, a strong relationship to the social movement and a tendency toward political activism. It is common for students and teachers there to participate in various political rallies. They usually transport themselves to them by commandeering public transport buses and directing them to their destination.

This was the case on September 26, 2014, when over a hundred students from Ayotzinapa seized several buses and took them to a commemorative event in Ciudad de México. But this time, not everything went according to plan. The local police cut off the buses in the town of Iguala and opened fire on them. Three students were killed. Some of the others were pulled off the buses by the police and taken to an unknown destination. In total, there are 43 students who have not yet returned home.

After heavy pressure from local people and foreign organizations, the then-attorney general came up with the version that the students had been executed by a local cartel and even presented several alleged perpetrators. The remains were said to have been burned in a dump and thrown into a nearby river. Such a story should have been enough for the public to silence the doubters. However, later investigations by foreign forensic specialists showed that it could not be based on truth for many reasons. Instead, suspicions of military involvement and links to the upper ranks of politics began to surface from various sources. The now-former attorney general, Murillo Karam, was arrested two years ago and accused of enforced disappearance, torture, and crimes against the administration of justice. He was recently released from detention to await the court's decision under house arrest.

It was the subsequent investigation that exposed the rampant corruption and the intermingling of organized crime with the state. Strings have been spun between local politicians, the police, the military, and the government. But the case was never completely closed, and all those involved were not brought to justice. Instead, Mexicans witnessed a despicable sweeping of evidence under the carpet, cover-ups, blame-shifting, and silly excuses.

Years later, Anabel Hernández, a respected Mexican journalist specializing in drug cartels, claimed that her findings showed that at least two of the buses the students commandeered were loaded with a $2 million shipment of heroin destined for the USA and that the order to stop them came from the military. The attorney general's indictment of specific individuals was fabricated to cover up the real perpetrators. The missing students were never found.

Streets in flames

The case has become a septic ulcer in the already quite crippled state of modern Mexican society. People can't forget this sore. And it's a good thing they can't forget it.

Furthermore, there is an anomaly in Mexico: people are actually fighting for their human rights. The locals will endure anything, low wages, and miserable living conditions, but when someone takes away their right to freedom and dignity, they won't be silenced. Here, when something stinks of injustice from above, they take to the streets. And the streets burn.

On the anniversary of the tragic event in Iguala, one of the most massive protests is held every year. This year, moreover, it was expected to be even more violent, as it was the milestone anniversary.

The protests therefore began on Monday, as I described above, even though the anniversary fell on the night of Thursday to Friday. After my belated visit to SEGOB that day, I still rushed to the main avenue, Avenida Paseo de la Reforma, where a resistance center dedicated to the events surrounding Ayotzinapa is permanently set up in a giant tent complex in front of the US embassy – yes, this is also common here, with permanent tent cities being set up in front of important institutions in protest.

About twenty buses from Ayotzinapa were parked along the boulevard, and the youth with typical bandanas around their necks or over their faces were just enjoying a simple lunch after a successful action with explosives. I learned from one of the guys standing by that another such event was scheduled for the next day, this time in front of the Attorney General's Office in the Doctores district.

As this is exclusive content, on which I have invested hours and hours of work, involving even some dangerous moments, the rest of the text is only for paying visitors. You will learn how I documented the violent protests over several days, and on top of that you can see a full gallery of the demonstrations. For six dollars you can also access all the other exclusive photo essays and the entire archive. You can then cancel your subscription at any time.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Václav Lang - Novinářem v Mexiku to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.