NOSTALGIA

A slightly borderline reflection on paths back. On the importance of places and moments we didn’t want to return to. And on the grand stories that belong to each of us.

“Don't come back. Don't give in to nostalgia. Forget about us.” Alfredo, Cinema Paradiso

Returning to old places usually warms a bit and hurts a bit. If, of course, we've left something of ourselves in there. It also depends on the conditions under which we left them and under which we return. Sometimes we just smile as the memory tickles us. It's the little things we laugh at nowadays. Other times our chests still ache - those are the scars that haven't healed yet. But it's always moments like these that make us think about who we were then and who we are now.

After more than seven years, fate brought me back to Tijuana, a border city in northwestern Mexico—the exact same place where I was spat out of the U.S. in the fall of 2017, with just one stuffed backpack, almost no money, a little hope, and no idea that I wouldn’t be coming back.

I'll never forget how, exhausted, I stepped out of the pedestrian border corridor into the afternoon heat and found myself in Mexico, in the middle of a deserted plaza, where nothing stood except a neglected fountain—only a tumbling ball of prairie grass was missing to make it feel like a movie scene. At the same time, in the eerie silence, I could feel many eyes on me, knowing it wasn't wise to linger here, especially looking like a Boy Scout who had just lost his troop.

I can see it now: me, sweating as I headed toward that fountain, fully aware that it was the most exposed spot. I tried to at least pretend I knew where I was going and what I was doing—though that was the thing I knew least of all. Meanwhile, I was discreetly hunting for a signal on my phone, trying to get anywhere near civilization as quickly as possible.

Now, after all these years, I had returned. Just as I did back then—to report on the refugees around the border wall. Fresh off Donald Trump's reappointment as president, once again a bit homeless and with no clear idea of what the next few weeks or months would bring. Though this time, in slightly better shape.

***

There are some things we can't erase from our memories: certain people, places, stories.

On Valentine's Day, it'll be a year since Krups left. Exceptional person, great mother-in-law, top journalist – one of the best around. The day after her death, obituaries across Mexico said she gave a voice to the voiceless—the forgotten ones.

I inherited piles of her books. Mostly stories about the local crime scene, then journalism and writing. A few days before leaving for Tijuana, I thought I should read some to get back in shape. One slim book caught my eye: Los Cínicos no sirven para este oficio (Cynics Are Not Suited for This Job). I wondered if it wasn’t the other way around—that maybe cynics should be doing this work, because then they wouldn’t be moved by the harrowing stories of individuals.

Still, I grabbed the book at the last minute and packed it for my Friday morning departure.

It was a set of interviews with the Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuściński. I'd never heard of him before. But the fact that he'd made it to this fine personal library somewhere in Mexico made me think it was probably worth paying attention to. Then, as we gained altitude and my nerves battled airborne vortices in the plane over the heated deserts of northwest Mexico, I took the book to the rescue and tried to drown out the tremors with focused reading. Certain passages were highlighted in pink—nearly all of them stressed the need for journalists to set aside their egos, seek out ordinary people, listen to individuals, and care about their small and big stories alike. That was exactly what I had set out to do.

Ironically, this was exactly what was on my mind the night before I left. For some reason, I felt nervous. That had never happened to me before—maybe I was out of practice. Or maybe the weight of responsibility had just fallen on me, because I had grown up a bit and was beginning to realise that I couldn't do this job like I did when I was "young" and just wait to see what happened on my first night in the pub. I was aware that I needed to do more. At the same time, a pall of doubt came over me, questioning: What's it all for anyway? No matter how sensational the news I bring, it will be old in a day or two. In a week, no one will remember it. People might pause for a moment, my ego would jump, but nothing would change.

But then there was an inspiration, a vision, that said the only way to make sense of it all was to direct it to the ordinary people. To those who have no representation elsewhere. To use the opportunities I have to help those in need. To care about those least heard, to immortalize their neglected stories and give them a voice.

Fortunately, I've had great partners to do that. The editors at revue Prostor magazine shared the same perspective: 'Take your time, we're not chasing a news story, but a story that will still matter in a few months.' That’s something rare today, as Czech media giants in the hands of businessmen won't allow it, there's no time for honest journalism, there's money to be made. So it's rare when you don't have to make fools of yourself and chase instant click-baiters, but you can go deep. Unfortunately one of the other natural consequences of capitalism.

Right next to the fact that those who don't have money and wealth right now automatically lose their voice and importance. Our proud quasi-Western society would rather hide them away so we can enjoy only the shiny stuff. I realized this as I hurried to catch a bus to the airport before dawn and passed homeless people on the benches. Such luxury is no longer available in our "developed" world. In fact, we're so progressive in Europe that they design benches so you can't lie down on them. So that those who are worst off have it even worse. Instead of spending money to help them get back on their feet, to show compassion, money is thrown away so we can pat ourselves on the back about how well we have it.

On the way to the airport, it was clear to me that this is exactly the kind of people journalists should be there for. To finally step out of the comfort of unhindered parroting of politicians, to stop being the mouthpiece of the powerful towards the people, and to become the mouthpiece of the neglected towards the upward.

***

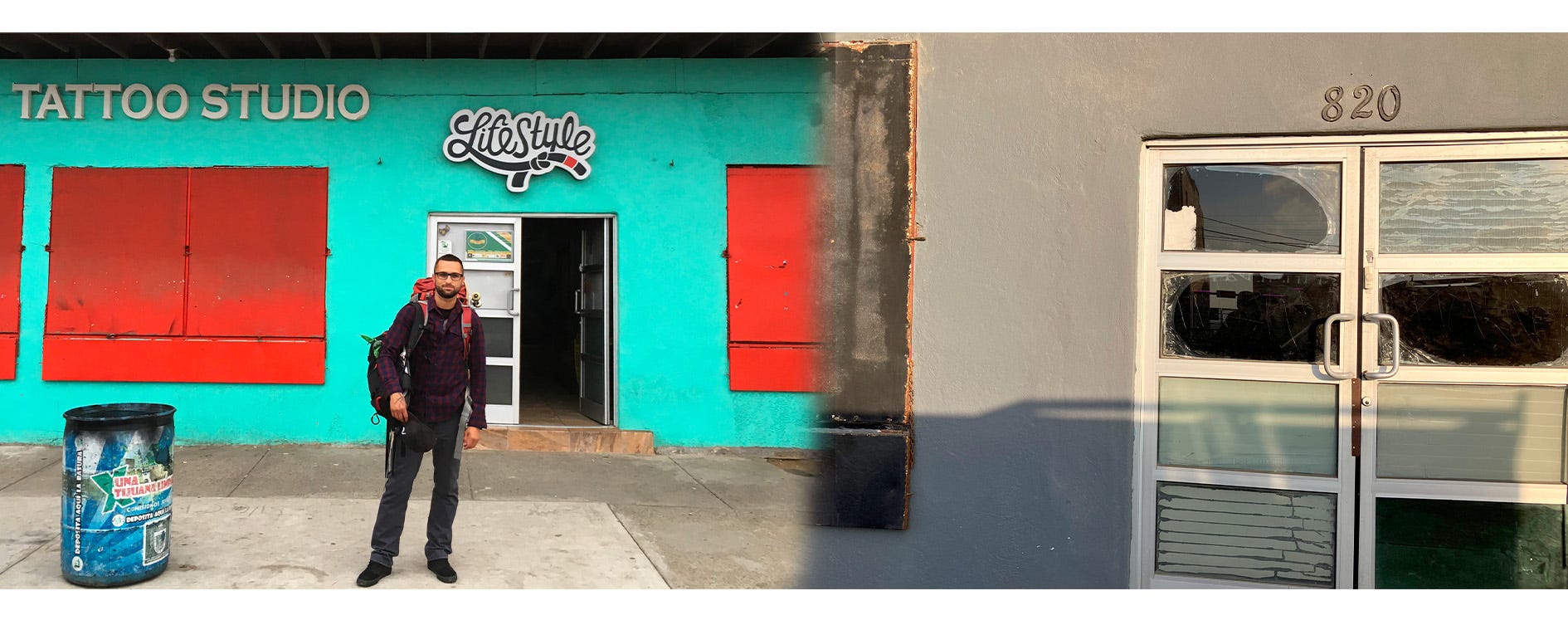

October 27, 2017. I wanted to get that date tattooed in Tijuana this year. To forever remind me that when all may seem lost, things can still turn around. A reminder that the only way off the bottom is up.

It was then that I went to Los Angeles to live my own 'American Dream,' which, however, didn’t happen, and so I wandered lower and lower until one day I found myself in Tijuana. I couldn't find a signal at the fountain there at the time, but I fit in at some shady grocery store where you could also get a beer, so I bought one and hooked up to the internet to arrange a ride to the coast. There, in the days that followed, I made a reportage from the border fence, where the eyes of the world were fixed at the time because of Donald Trump's freshly begun first term as president.

Even though for a while it looked like I was doing something that mattered again, even though I was sending stories to the Czech Republic of people who had everything taken away by the fence, it didn't increase my chances of success overseas. I was sleeping in a hostel with a bunch of perpetually drunk retired Mexican-Americans, eating mostly defrosted pizza from a nearby 7Eleven, and my dream of success in the big world was slowly but surely turning into a nightmare. Luckily, the roommates were pretty fun and there was also a Wallmart nearby where I got a bottle of mezcal for 159 pesos.

The plan was to get acclimated in Tijuana, do my reportage, and go to Ciudad de México for a Día de Muertos. There I would see my girl that time, the daughter of the aforementioned mother-in-law, and probably return to America again. But when I bought the tickets on that date and saw my account balance, I wanted to cry. I knew that I had only a few weeks of hope left, then I would have to call it a day. There's no way I can survive this. The image of returning to the Czech Republic after my grand departure, three months later, with a plea popped into my mind. How I’d have to go back to my old job at the bizarre news factory and probably live in my friends’ places.

Today I know it would be no shame. That it's moments like these that create strong characters. But back then? Back then, I felt like shit.

I bought a plane ticket and shook off the gloom. I knew that now I could only hope that one of the jobs I'd been looking for all this time would finally come out. And if not? I guess I didn't really have anything to lose.

I uncapped the bottle of mezcal and drank shot after shot in that blissful despair. Not even to induce drunkenness or oblivion. On the contrary, it didn't get me drunk at all. But it felt good to laugh at myself as I did.

Pretty soon, I was almost at the bottom of the bottle, and at that moment, I corked it: Not yet, mate, you can't give up yet, you're not at the end yet. You have to hit the rock bottom first, and then it will come and it will be a blessing, because then it will kick you up! And I decided to hope for a little while longer.

That night, I went to bed with a clarity I hadn’t felt in a long time and woke up with a brutal hangover. I checked my phone and, at first, couldn’t tell if it was the agave talking. There was a message from the guy who ran a hostel in the Yucatán, the one I’d been trying to get into for weeks: 'Come, the season’s starting, we could use all the help we can get!' Before I could get too excited, another message came in, from a friend at Czech TV, asking me to go live and share my experience from the border wall.

That day a new story of my life began to be written. I shot the promised interview in a living room in Ciudad de México, which soon became my new home. In the meantime, I also spent some time in Tulum, Yucatán, and also received other job offers.

Seven years have passed since that unfortunate night and blessed morning in October, most of which I have spent in Mexico and much of which I have been able to engage in activities that make sense to me. Would I have thought then that I would be where I am today? Certainly not. I am far from where I would like to be: still haven't published the book, still not the acclaimed author, still on the road, etc. I've lost out on a lot of things, but I'm alive and still heading up. And that's the biggest win.

So on the third Friday of this year, I stood in Tijuana again. At the airport, seven years older. Seven years more experienced, with far more scars on my soul, a little more knowledgeable and a little less reckless. I'm also a little calmer, because I've learned that everything always sorts itself out at the end and there's no point in hoping for the worst.

The taxi driver laughed – he said this was a completely different city than I knew it, because it was growing at a breathtaking pace. But honestly, all I remembered from my brief visit years ago was the hostel and the nearby promenade to the border fence. And it will still be there, I'm sure. And then there were the memories of those few harrowing nights.

I drove downtown to the hotel - yes, there was no longer a bed waiting for me in a cot for twenty tattooed regulars - and headed straight for the border. I wanted to go right to the border crossing - where the immigrants go to negotiate their entry into the US. I had the place picked out from the news, it was called El Chaparall.

I shivered when I got there. Half-dead homeless, hookers, drug addicts everywhere... Good thing I left my camera and the rest of my gear at the hotel for the day. When I pulled out my phone to look at the map, I didn't feel good at all. But I finally hit the bridge over the Río Tijuana, at the end of which was supposed to be El Chaparall.

Down below, armed National Guard men were just handing out junkies from the neighborhood. I climbed up onto the bridge and saw the dry riverbed and the skyline of the big city. On the other bank, a rusty fence loomed on the horizon, and beyond it, an American flag. I advanced on the bridge, wondering when I would be ambushed. I'm like a fist in the eye again, just like I was then, though not as naive as a Boy Scout.

When I got to the other half of the bridge, I was no longer in doubt. Something must have dropped in my eye. I was staring ahead and actually looking back. A few more steps and a desolate and deserted square with a neglected fountain in the middle opened up in front of me. Yes, the very place where I had found myself seven years and a few months ago, with just one stuffed backpack, almost no money, a little hope, and no idea that I wouldn’t be coming back.

I stopped and stared at the fountain where I had parked back then, sweaty and scared, trying to figure out how to escape that despair. I realized that I truly had no idea where I was going or what I would do. The only certainty was that I’d keep trying to survive for a little longer before my dream ate me alive. I smiled at the thought, maybe to comfort my younger self from a distance: 'It’ll be okay, buddy, we’ll get through this.

I walked down to the little square, looking for the store where I had once taken refuge. But everything around seemed even deader than before. So I headed straight for the border crossing—the spot where, years ago, homeless Nick was supposed to be waiting for me with his van to take me to the beach. I instantly recognized the parking lot where we met, where he poured out a bucket of urine from his van. And where the border guards with machine guns were yelling at us. And where I thought to myself: What the fuck have I got myself into again!

I had a beer in another one of the local shops, with a view of the fountain. It didn’t feel much safer than back then, but now I knew how to get out of trouble. I spoke Spanish, had a phone with a local provider so I didn’t have to search for Wi-Fi, had enough money for a taxi, and plenty of contacts. After all, I also knew exactly where I was. And why.

It felt almost surreal. I wished I could hug my small, frightened self and tell him there was nothing to fear. That it would be tough, that along the way he’d lose a lot—strength, loved ones, ideals, and more. That he would suffer immensely, but that there would also be moments of hope, love, and good people. Moments that made it worth having that second-to-last shot and simply believing that things would turn around once again.

***

I went to the coast the next two days as well. The building where I lived in October 2017 was lifeless, the windows boarded up, the signs torn down and the door held only by force of will. The guy in the shop next door had no idea there had ever been a hostel there. "I've only been here six years," he told me.

The building across the street was burned down, but the same 7Eleven I used to go to for cheap pizza was still there. And also Wallmart, where I bought a Fandango mezcal the other day, which I would probably only drink today out of nostalgia.

Of course, I also visited the border fence, where I had once desperately searched for stories for my report. And I was grateful that I could now do this work in a way that not only shocked but also helped. With every interview I conducted there, I thought of Krups, and that Polish journalist, and the importance of remembering those most in need—to be their voice.

Because great stories are made up of seemingly small people and their seemingly insignificant stories. We all live out our own dramas, and none are greater or lesser than others. As journalists, we should focus on these stories. And as human beings, we should never lose hope—because even when we feel like we've hit rock bottom, the bottom is there for a reason: to push us back up to the surface. No matter how impossible that may seem in the moment.